NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) has successfully hit its asteroid target, Dimorphos, and altered its trajectory.

At 1.14am on Tuesday 27 September 2022, the Dart (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) spacecraft deliberately hit the smaller of the two asteroids in the Didymos – Dimorphos binary system, redirecting its trajectory.

The mission

The collision, which occurred at a speed of 24,000 kilometres per hour (6 kilometres per second), took place in space, some 13 million kilometres from Earth.

NASA’s mission, which cost just over $300 million, was a simple test to see if the course of an asteroid could be altered, and it was a first. A real “space buffer“, organised down to the last detail and without any risk to our planet, which had the merit of testing for the first time a technology that could, in the future, protect us from a possible collision with a dangerous asteroid. A real test of planetary defence.

The Dart spacecraft, which will leave Earth at the end of November 2021, was designed, built and operated by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory with support from many Nasa centres. It is an important part of the Aida (Asteroid Impact and Deflection Assessment) mission, a collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency (Esa).

An exciting impact

Weighing just 570 kilograms, DART targeted the asteroid moonlet Dimorphos, a small body just 530 feet (160 meters) in diameter, roughly the size of the Colosseum. It orbits a larger, 2,560-foot (780-meter) asteroid called Didymos.

As it approached its target, Dart sent back to Earth increasingly detailed images of the asteroid’s surface at a rate of one frame per second, collected by its optical camera, called Draco. These spectacular images showed Dimorphos growing larger and larger as it approached Dart, until the last image was taken just before the crash that destroyed the spacecraft.

It is these final images that are the most exciting, because they show the morphology of the asteroid and its finest details, just a few metres from the surface. The last image captured by Dart’s Eye, which was only partially transmitted to Earth before impact and will forever remain incomplete (although the small part collected shows a very high level of surface resolution), is particularly significant.

With each close-up, the excitement in Nasa’s control centre grew, culminating in the huge applause that greeted the impact. “The resolution of the images we collected was beyond our expectations“, said mission coordinator Nancy Chabot immediately after the impact.

The first images

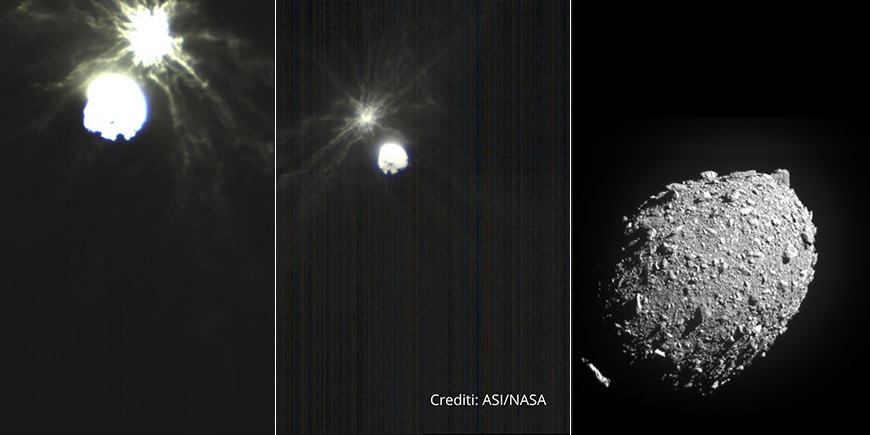

As the spacecraft approached Dimorphos and the excitement in NASA’s control centre became more and more palpable, a small Italian witness – LICIA-Cube – was filming the impact.

It is a small satellite, about the size of a shoebox, built by the Italian Space Agency (ASI) and the Turin-based company Argotec, which travelled with Dart for almost a year before separating a fortnight ago and positioning itself about a thousand kilometres from impact.

‘It was a spectacular impact!’ Simone Pirrotta, LICIACube mission manager for ASI, who followed the mission from the Turin Control Centre, told Ansa. ’The Dart spacecraft’s SmartNav guidance technology worked to perfection. Here in Turin, we watched the end of the NASA mission with excitement, knowing that our little reporter was documenting a historic moment: the first time mankind has changed the orbital state of a celestial body. ’, he added, referring to the LICIA-Cube satellite.

The first images taken by the mini-satellite immediately after the impact, which were presented at a press conference at Argotec, show Dimorphos surrounded by a cloud of debris from which rays of dust emerge, brightened by the sun’s light and in stark contrast to the absolute darkness of deep space. In front of the dust cloud, Didymos, the larger of the two asteroids, watches helplessly as Dart collides with its small moon.

And now?

Dart’s impact with the asteroid marked the beginning of the next phase of the mission: the analysis of the data sent back and the evaluation of the impact, which will take at least several months.

Obviously, given the huge difference in mass between the two bodies involved in the impact, the deflection of the asteroid cannot be enormous. Initial estimates predict a slight approach of Dimorphos to Didymos, which should reduce the orbital period, the time it takes to complete each revolution around the asteroid, by about ten minutes.

Nasa’s mission systems engineer, Elena Adams, said: ‘Over the next few months we will have more information from the investigation team about what kind of trajectory change we actually caused, because that is our number two goal. Number one was to hit the asteroid, which we did ‘.

In addition to LICA-Cube and terrestrial telescopes (including Hubble and James Webb), another European-built satellite – Hera – currently under construction but due to be launched in October 2024, will observe the asteroid Dimorphos in 2026.

So keep your eyes on the sky!